Trump administration tells Congress war law doesn’t apply to cartel strikes

The Office of Legal Counsel told select lawmakers that the executive branch is not bound by the War Powers Resolution, which requires congressional approval for any military action that exceeds 60 days.

November 1, 2025 WPost

President Donald Trump has said that the boat strikes in the Caribbean may expand to include targets on land, at times suggesting he may hit Venezuelan territory. (Demetrius Freeman/The Washington Post)

By Ellen Nakashima and Noah Robertson

A top Justice Department lawyer has told lawmakers that the Trump administration can continue its lethal strikes against alleged drug traffickers in Latin America — and is not bound by a decades-old law requiring Congress to give approval for ongoing hostilities.

T. Elliot Gaiser, head of the Trump administration’s Office of Legal Counsel, made his remarks to a small group of lawmakers this week amid signs that the president may be planning to escalate the military campaign in the region, including potentially hitting targets within Venezuela.

The president needs lawmakers’ approval for sustained military action under the 1973 War Powers Resolution, which was passed in the wake of the Vietnam War to prevent another drawn-out, undeclared conflict.

A 60-day clock started ticking after the administration informed Congress on Sept. 4 that it had conducted a strike on an alleged drug boat in the Caribbean two days earlier. It has followed that with other strikes and has killed dozens of people.

Gaiser said the administration did not believe the strikes met the definition of hostilities under the law and did not intend to seek an extension of the deadline nor Congress’s approval of ongoing action, according to three people familiar with the matter, who, like others interviewed for this article, spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the matter.AI Icon

“The administration appears to be blowing through the 60-day limit,” a senior congressional aide said.

Asked for comment, a senior administration official said the War Powers Resolution did not pertain to the current situation, because, “even at its broadest … [it] has been understood to apply to placing U.S. service-members in harm’s way.”

The official said the administration does not believe U.S. troops are in danger in the ongoing operation, so the law did not apply. “The operation comprises precise strikes conducted largely by unmanned aerial vehicles launched from naval vessels in international waters at distances too far away for the crews of the targeted vessels to endanger American personnel,” the official said in an email.

In essence, the official said, “the kinetic operations underway do not rise to the level of ‘hostilities.’”

National security experts challenged the administration’s interpretation.

“What they’re saying is anytime the president uses drones or any standoff weapon against someone who cannot shoot back, it’s not hostilities‚” said Brian Finucane, a former legal adviser to the State Department who is now a senior adviser for the U.S. program at the International Crisis Group. “It’s a wild claim of executive authority.”

If the government ignores the Monday deadline, he said, “it is usurping Congress’s authority over the use of military force.” Under the Constitution, only Congress can declare war.

Finucane was the War Powers Resolution lawyer at the State Department in the Obama and first Trump administrations. During that time, standoff strikes were carried out on Houthis in Yemen in 2016, as well as against Syrian military facilities in 2017 and 2018 in retaliation for President Bashar al-Assad’s use of chemical weapons against civilians. In both cases, Finucane said, the actions were considered hostilities activating the War Powers Resolution.

Both Democratic and Republican administrations over the years have “used creative interpretations of the law to skirt the deadline,” he said, but they were not targeting civilians who are not at war with the United States. “When the U.S. was bombing Libya in 2011, there was an armed conflict,” he added. “That’s not the case here.”

Finucane noted that by notifying Congress on Sept. 4 that it had conducted a strike on an alleged drug smugglers’ vessel, the administration appeared to have taken the position that the strike had triggered the 1973 law and that Congress’s approval would be needed to continue action beyond 60 days.

In the Sept. 4 notice, President Donald Trump said he was submitting it “to keep the Congress fully informed, consistent with the War Powers Resolution.”

Defense Secretary James Schlesinger said in 1973 that the war powers legislation passed by Congress may make it possible for President Richard M. Nixon to order new bombing in Indochina in the event of a major North Vietnamese offensive in South Vietnam. (Jim Palmer/AP)

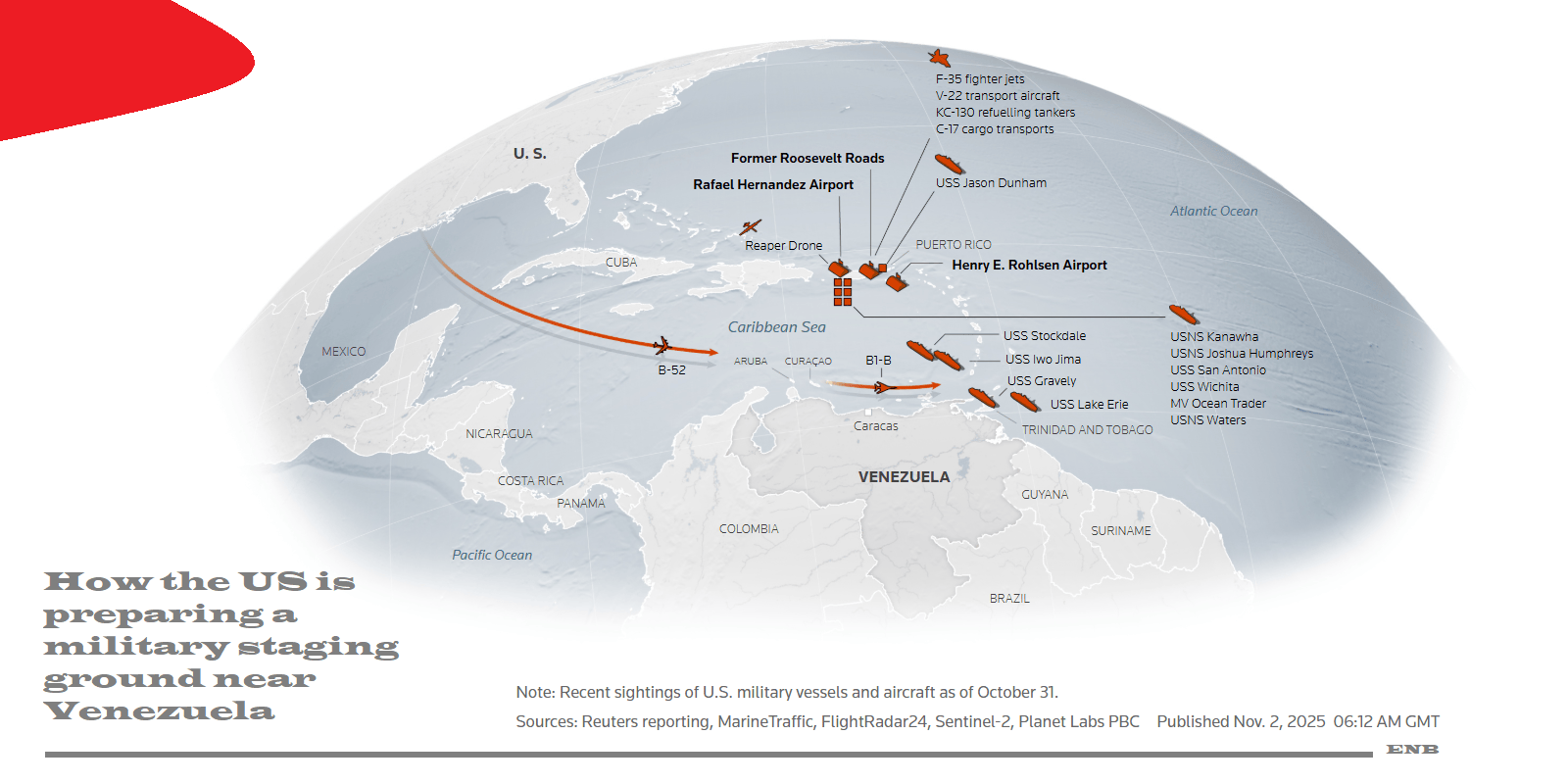

As the deadline approaches, there is no sign that the administration is curtailing its strikes. It has carried out more than a dozen strikes on boats in the Caribbean Sea and the eastern Pacific Ocean, and has surged an array of military assets into the region.

The Navy has eight warships in the Caribbean, about 10 percent of its deployed fleet. That includes several destroyers and two amphibious ships. A submarine and a Special Operations vessel carrying helicopters also are in the region, and an aircraft carrier and several more destroyers are on the way. The military has flown helicopters and bombers close to Venezuela multiple times and moved F-35s and other aircraft to Puerto Rico.

Trump has said repeatedly that the boat strikes may expand to include targets on land, at times suggesting he may hit Venezuelan territory. “We are certainly looking at land now, because we’ve got the sea very well under control,” he said.

On Friday, however, when asked whether he was considering strikes within Venezuela, he told reporters, “No, it’s not true.”

The assertion that the administration is not bound by the War Powers Resolution or obliged to seek Congress’s permission to continue its campaign is consistent with Trump’s aggressive expansion of powers at the expense of the other two branches of government, observers said.

Separately, in a classified Office of Legal Counsel opinion, considered binding by the executive branch, the administration has argued that the strikes advance an important national interest and do not rise to the level of war under the Constitution and, therefore, do not require congressional approval, according to one U.S. official.

This week, top administration officials excluded senior Democrats when they briefed a handful of Republican senators who are considering whether to support a bipartisan measure that would block direct attacks on Venezuelan territory.

“In any normal administration, somebody would be fired for this kind of abuse,” Sen. Mark R. Warner (Virginia), the top Democrat on the Senate Intelligence Committee, said in a news conference.

On Friday, Warner and other leading Democrats who focus on national security demanded that the administration brief the full Senate on the strikes.AI Icon

Sen. Roger Wicker (Mississippi), the top Republican on the Senate Armed Services Committee, joined in a rare bipartisan rebuke the same day. He and his Democratic counterpart, Sen. Jack Reed (Rhode Island), made public two letters they had sent to the Pentagon weeks before, requesting legal documents, attack orders and a list of targets. The Defense Department, they wrote, had exceeded the amount of time required by law to provide some of the materials.

House members were visibly frustrated after a separate classified briefing on Thursday, arguing that administration officials failed to answer basic questions about the legal basis and intelligence supporting the attacks. Pentagon lawyers had been scheduled to attend the meeting, multiple lawmakers said, but were abruptly pulled back without explanation.

“The administration is, I believe, doing an illegal act and anything that it can to avoid Congress,” said Rep. Gregory W. Meeks (New York), the top Democrat on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, who attended the briefing.

Several lawmakers said Thursday that the Pentagon relayed that it did not need to know the identities of those being targeted in the attacks or whether those killed had been trafficking drugs.

“What they told us is they have to show a connection to a designated terrorist organization or their affiliate, and as long as they can show that connection, they believe they are authorized to strike,” Rep. Sara Jacobs (D-California) said in an interview.

But such connections could be as much as “three hops away” from a known drug trafficker, Jacobs told reporters after the briefing.

Lawmakers said the military official leading the House briefing, Rear Adm. Brian Bennett, rejected Democrats’ observation that the way the administration was selecting targets resembled “signature strikes.” That is a practice the CIA used for years in Afghanistan and Pakistan when it launched drone attacks on individuals or groups whose identities were unknown but who were targeted based on a pattern of behavior or other characteristics associated with terrorist activity.

Jacobs also said that the administration privately acknowledged that cocaine was the primary drug trafficked in this part of the world — contradicting Trump’s claims that the strikes are protecting U.S. citizens from the spread of fentanyl.

“They tried to make a very convoluted argument about why cocaine was facilitating drug trafficking,” she said. “It seems to me they don’t actually understand how fentanyl works.”

Rep. Seth Moulton (D-Massachusetts) told reporters after the briefing that he warned the administration about its expansive use of military force.

“The last word that I gave to the admiral is I hope you recognize the constitutional peril that you are in, and the peril you are putting our troops in,” Moulton said.

Dan Lamothe, Alex Horton and Karen DeYoung contributed to this report